Introduction by Joseph Wrzos

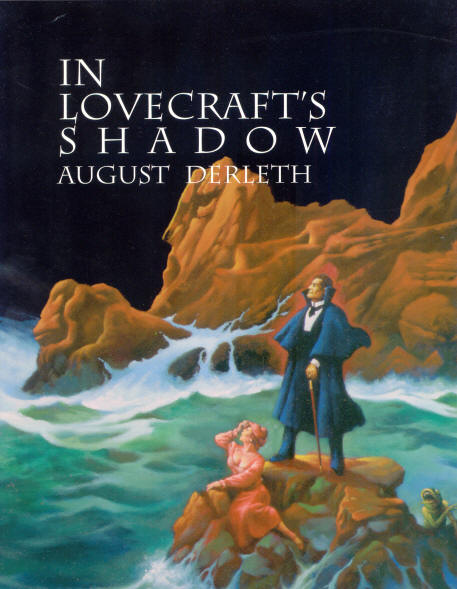

Illustrations and Cover by Steven Fabian

Folio

Black Buckram Hard Cover with wrap around Dustjacket, 366 pp.

ISBN 1-55246-003-7 @ $75.00

Introduction by Joseph Wrzos

[Note: For all stories cited below (except those by H.P. Lovecraft referred to

here and in the "Notes" section), dates given are for first publication, in some

instances not necessarily the year of composition.]

In the autumn of 1928, when August William Derleth, still only a junior at the

University of Wisconsin, wrote to A. Conan Doyle, asking if Sir Arthur

contemplated writing any new stories about Sherlock Holmes, Doyle (his terse

response scrawled across Derleth's own returned letter) replied emphatically in

the negative.

However, it's doubtful if the world-famous British author

recognized (or would have appreciated knowing) that this latest missive from

America was not just another typical "fan" letter. For his young American

correspondent, though almost completely unknown in the literary world at that

time, was nevertheless already a published writer. By then, at least a dozen of

his fledgling efforts had appeared in early issues of Weird Tales, the now

almost legendary pulp, the first of them, "Bat's Belfry" (May, 1926) seeing

print when Derleth was still in his teens. Derleth, characteristically, with or

without Sir Arthur's blessing, went on to write his own Solar Pons stories.

"Fond and admiring" pastiches, he was careful to call them, eschewing parody as

a form of ridicule unworthy of the Great Detective.

During this same period, however, even before writing to

Doyle, Derleth was already corresponding with Rhode Island author H. P.

Lovecraft, a fellow but senior contributor to Weird Tales, whose own early

stories (such as "The Outsider" [1921], "The Rats in the Walls" [1923], and,

particularly, "The Call of Cthulhu" [1926]), the neophyte Wisconsin writer

perceptively recognized as having literary worth transcending their pulp

origins.

Unlike Doyle, however, Lovecraft kept up a steady (and

incredibly voluminous) correspondence with a small group of talented and

aspiring pulp writers, among them Frank Belknap Long, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert

E. Howard, Henry Kuttner, Robert Bloch and, of course, young Derleth.

Furthermore, never proprietary or testy about his work, Lovecraft also actively

invited his acolytes to expand upon the Mythos he was gradually but loosely

developing with such classic tales as "The Call of Cthulhu" (1926), "The Dunwich

Horror" (1928), The Shadow Over Innsmouth (1931), and At the Mountains of

Madness (1931), to cite only a few of the most seminal.

Easier said than done. For the Lovecraft Mythos has been the

subject of intense critical debate, especially of late, between the "Purists,"

on the one hand, who insist that the original premise remain intact, even though

the author never developed it systematically, and "Revisionists" (principally,

Derleth) bold enough to tinker with it for their own devices. As argued by the

former, Lovecraft's Mythos, indirectly reflecting his own essentially nihilistic

views, is based on the idea that the unbounded universe, despite Man's ignorant

pretensions to the contrary, in actuality is dominated by the Old Ones, cosmic

beings (such as Yog-Sothoth and Cthulhu) completely indifferent to Mankind's

"little drama," who might at any time choose to shut it down.

"Revisionists," on the other hand, tending to ignore

Lovecraft's "dark mind-set," apparently feel free – according to their needs –

to organize his concepts into a more manageable whole. Derleth, for instance –

along the way suggesting a possible Christian Mythos parallel – has even gone so

far as to polarize Lovecraft's Old Ones. Subdividing them into Elder Gods (the

"forces of good") and the rebellious Great Old Ones (the "forces of evil"), the

former – long before the advent of Mankind – defeating their noxious brethren (Cthulhu,

Hastur, Nyarlathotep, and the like) and "imprisoning" them at various points in

our galaxy. In Cthulhu's case, for example, Earth, where he lies dreaming

beneath the sea in sunken R'lyeh, located either off Innsmouth's Devil Reef (in

New England) or the Northern Pacific's Ponape, in the Carolines.

As if this weren't radical enough, Derleth – some have

protested – has also gone too far by attempting to classify the Great Old Ones

into groups of Elementals, beings (according to Medieval belief) akin to the

"spirits" thought to reside within Earth's four basic elements. Thus, Cthulhu's

realm became "water," Ithaqua's "air," and so on. Not a viable departure from

Lovecraft's original premise, however. For his Old Ones are clearly of

extraterrestrial origin, and cannot be thought of as being "confined" to Earth

alone, whether in an elemental milieu or otherwise. As a consequence, in some of

his Mythos stories, Derleth found it necessary either to sidestep this

inconvenience or gloss over illogical inconsistences by inventing a god or two

of his own. For example, the air elemental Cthugha, in "The Dweller in

Darkness."

Nevertheless, whether a Derleth Mythos story adheres to or

departs from the original Lovecraft "design," it usually centers on "first

contact," belated though it be, between Mankind and the Great Old Ones –

"aliens" from elsewhere, dominant on Earth before mankind! Most often Cthulhu,

his spawn or his minions. Such encounters often involve an inquisitive scholar

or some unwitting descendant of Innsmouth miscegenation. Whose researches into

"forbidden texts," commonly the dread Necronomicon and at times the Confessions

of the Mad Monk Clithanus (a favorite Derleth device) invariably lead to

traumatic revelations and hideous consequences for the overly persistent.

The Lovecraft challenge, then, was indeed formidable for any

acolyte, whether during H.P.L.'s own lifetime or in the years following his

early death. But a good number of them rose to the occasion, their variations on

the Mythos theme (particularly those by Smith, Howard and Long) still worthy of

the Canon. As are Derleth's own Mythos tales, particularly if taken as a whole,

one of the prime considerations for making them available once more in this

special, illustrated edition.

Even so, it must be admitted that Derleth's first (published)

attempt to pay homage to Lovecraft (written during the latter's lifetime) was

far from auspicious. "Those Who Seek" (Weird Tales, January, 1932) proved to be

minor and derivative formula writing. The English artist, the ruined abbey

(inexplicably "shifting" in time), the terrifying dreams of long-dead monks

making blood sacrifice to a huge gelatinous "thing," tentacled, green-eyed – all

this, even then, was overly familiar. However, it was suggestive of Cthulhu, or

one of his minions, and at least it was a start.

Concurrently with these early attempts at emulating Lovecraft,

Derleth, one summer in 1931, in collaboration with his Sauk City boyhood friend

Mark Schorer (later to make his own Mainstream mark as novelist, short story

writer and biographer), churned out at least a dozen "chillers" aimed

unabashedly at the pulp horror story market, most of which sold, though not

immediately. Of these, "Lair of the Star Spawn" (1932), "Spawn of the Maelstrom"

(1939), and "The Horror from the Depths" (1940), though far from the first rank,

are very much in the Mythos vein, and worth attention.

In all three narratives (possibly due, in part, to Schorer's

influence), unlike the traumatized artist in "Those Who Seek," the protagonists,

facing a more immediate Mythos threat, gamely try to fight back. In "Star

Spawn," for instance, the Chinese doctor Fo-Lan and Eric Marsh (a scion of the

Innsmouth line?) both prisoners of Burma's Tcho-Tcho people, nevertheless manage

to foil the "little men's" plans for "releasing" Lloigor and Zhar (Great Old

Ones). Doing so by enlisting the aid of the the Star Warriors of the Ancient

Ones, sent from far Orion, and by the arrival of the Elder Gods themselves! Even

today, however, such direct intervention from the stars is rare in a typical

Mythos story.

Narrowing the focus considerably, the two young

collaborators, in "Spawn of the Maelstrom," export Mythos menace to the British

Isles, where two upper-class Englishmen manage to "disintegrate" a monstrous

"undying creature" (allegedly spewn up from the depths of the earth by the sea),

which has usurped the form of an eccentric scientist friend. They do so by

wielding a "star-stone" bearing the seal of the Elder Gods, an almost ubiquitous

plot device in many of Derleth's later solo stories in the Mythos cycle.

Centrally so, in "Something from Out There" (1951) – another of the author's few

"English" Mythos pieces – where it provides the only means for re-entombing

Cthulhu spawn. And pivotally, in the postwar-written Laban Shrewsbury series

(collected as The Trail of Cthulhu, Arkham House, 1962), in which Derleth

concocts ingenious deployments for the star-stone.

This Elder Gods talisman also appears prominently in "The

Horror from the Depths," the last of the Derleth-Schorer Mythos collaborations.

For it is the only weapon available to Professor Jordan Holmes (the surname

perhaps a tipping of the hat to Doyle) and the unnamed narrator for driving

Cthulhu's monstrous spawn back into watery confinement in Lake Michigan, from

which dredging for the 1939 World's Fair had inadvertently freed them.

Interestingly enough, though "Horror from the Depths" did not

finally see print for nine years, it is the only Derleth-Schorer collaboration

from that period to mention not only the Necronomicon but Derleth's Elder

Gods/Great Ones revision as well. But if these details were actually included in

the first draft of the story (written ca. 1931), this would suggest that the

young Derleth (who later claimed responsibility for the plots worked out in the

collaborations) had begun tampering with Lovecraft's Mythos substructure, even

while his mentor was still alive and developing it further in his own writing.

But that's hardly likely. Probably, by decade's end, after he

and Schorer had gone their separate ways, Derleth himself – then more confident

with the Mythos framework – heavily revised "Horror from the Depths," bringing

it "up to date." If so, the "modernized" version apparently wasn't original

enough for the author's usual market, Weird Tales, for instead it appeared in

Strange Stories, one of the latter's rivals.

From 1932 onwards, however, Derleth's Mythos work was done

solo. Except for the later Lovecraft "collaborations" – The Lurker at the

Threshold (1945) and The Survivor and Others (1957) and a Robert E. Howard

fragment (or outline) which Derleth "amplified" for publication in 1971, the

year of his own death. However, his own initial attempts, in the ‘30's, were

crafted very much under Lovecraft's eye, so to speak, for the two writers

continued corresponding until the latter's sudden death in 1937. After which,

Derleth's subsequent Mythos stories (whether solo or "collaborative") took shape

always in his mentor's shadow. The challenge, implicit every time he began a new

Mythos variation, must have been daunting, but over the next two decades Derleth

was to face it, time and again.

Derleth's second solo Mythos effort, "The Thing That Walked

on the Wind" (1933), was heavily influenced by "The Wendigo," Algernon

Blackwood's classic Wind-Walker story. It is also liberally sprinkled with

Mythos references (to Lovecraft himself, to Cthulhu, R'lyeh, and the forbidden

Plateau of Leng). Set in Manitoba's North Woods, it recounts the inexplicable

disappearances of a few local residents, apparently "plucked up" into thin air

and never heard from again. Until a Royal Mountie investigates, and several of

the "missing persons" (cocooned in ice but still alive!) begin dropping back

down out of the sky (a possible Fortean influence at work here).

Although at first, the garbled and feverish ravings of a

survivor fail to convince the Mountie, soon enough he too sees Ithaqua, the

Wind-Walker, and is snatched up in his turn. Eight years later, in "Ithaqua"

(1941), Derleth would return to the circumstances depicted in "Thing That Walked

on the Wind." But instead of making it a sequel, he virtually "retells" the

original story, adding nothing whatsoever new on the subject.

But in 1939, Derleth did much better by the Mythos. "The

Return of Hastur" – prominently featured, though not the cover story itself, in

the March issue of Weird Tales – is prudently set in the outskirts of Arkham and

evokes much of the same outré atmosphere so pervasive in Lovecraft's best

Arkham-Dunwich-Innsmouth tales. The basic circumstances of the story are also

still Mythos familiar. Old Amos Tuttle, a now-dying New Englander, after

studying all the requisite "forbidden texts," learns all about the Old Ones, but

still needs to consult one of the most important but elusive volumes. In order

to acquire it, however, he must make a sinister but unspecified "promise" to

Hastur, and he does.

At this point, however, Derleth gives the plot a novel twist.

For Amos tries to renege on his "promise," both by dying before it can be kept

and by specifying peculiar conditions in his will, instructing his heir to

destroy the dead man's library of esoterica and demolish Tuttle House as well!

But nephew Paul has no intention of honoring so singular a bequest. Instead, he

moves into Tuttle House, dips recklessly into the unholy texts and, following in

his uncle's footsteps, in due course himself is claimed by an Old One. This

time, however, it is Cthulhu, not Hastur, though the latter is not to be denied.

In a literally explosive climax, in which Tuttle House is blown to pieces,

Hastur arrives on Earth, flinging his adversary Cthulhu far back out to sea, and

is ready to claim his due. If not the uncle, then the nearest kin will have to

suffice, and that means hapless Paul, who by then, like his deceased uncle

before him, has metamorphosed into a batrachian monstrosity!

All these novel plot flourishes in "The Return of Hastur,"

only his third Mythos effort alone, reflect Derleth's still respectful but

increasingly revisionist attitude towards the Lovecraft legacy. An emerging

difference in view that becomes more pronounced in "The Sandwin Compact"

(published the following year, also in Weird Tales). In this fourth variation,

three generations of Sandwins have profited financially from a pact made with

the Old Ones, the fine print most likely worked out with the latter's minions.

The terms of the agreement stipulate that each generation, with no right of

appeal, "sign away," the next into bondage to the Old Ones.

Finally, Asa Sandwin, the current head of the family, decides to end the family

curse and spare his son Eldon from a lifetime (and "more"!) of abominable

servitude. Hideously transfigured but confident of success, Asa stops up all

access to his room and waits – but overlooks a small windowpane crack in the

attic above. And fails, of course, when Lloigor the Old One (see Derleth-Schorer,

"Lair of the Star Spawn") comes for him, sucking the rebellious Asa right out of

his clothes, discovered horribly vacant and draped across a bedroom chair. But

even though he failed to outwit the Old Ones, as a father Asa succeeded, the

attempt alone serving to free his son from the family curse. A note of paternal

compassion more typical of Derleth than of his mentor.

During the Second-World-War years, however, Derleth relocated

his next Mythos stories Midwestward again, setting "Beyond the Threshold" and

"The Dweller in Darkness" (both published in Weird Tales, "Threshold" in 1941,

"Dweller three years later) deep in the Wisconsin's North Woods. Although each

story basically recapitulates the standard Mythos plot (overzealous researcher

swallowed up by Old One), of all the author's Lovecraft homages, "Beyond the

Threshold" and "The Dweller in Darkness" are the most richly atmospheric,

exhibiting all the considerable narrative and descriptive skills which Derleth,

by then a noted regional writer, had begun to hone at this stage of his career.

Once more, in typical Mythos fashion, an overly curious

scholar or adventurer stumbles upon the way to the Old Ones. In "Beyond the

Threshold" (the first published of the two), it is willful Josiah Alwyn, an

adventurous but elderly world traveler, who gets too close to Mythos "truth"

when he minutely studies cryptic papers left by a relative (Uncle Leander of

Innsmouth!). In "The Dweller in Darkness," it is Prof. Upton Gardner – a

collector of "place legends" – who, while investigating reports of a local

"monster" sighted in the North Woods, suddenly finds himself confronted by

Nyarlathotep, an Old One without a face! Derleth also injects an element of

suspense in both tales by keeping each protagonist in the dark as to exactly

which Old One he is dealing with. Doubts soon end, however, when one windy night

Ithaqua plucks Old Josiah right out of his bed, and Nyarlathotep (the Crawling

Chaos) completely ingests the hapless professor, condemning him thereby to a

"living death" and endless servitude to the Dweller in Darkness.

There is, however, a striking contrast between the endings of

these two North Woods Mythos stories. Published three years earlier than

"Dweller" (in the same year as "Ithaqua," in fact), "Beyond the Threshold," not

unexpectedly, ends very much like the author's first attempts at transplanting

New England Mythos to Wisconsin woods. For, in a final note, it is revealed that

seven months after old Josiah Alwyn mysteriously disappeared from his room one

windy night, his body was found, inexplicably far from Wisconsin, "... on a

small Pacific island not far southwest of Singapore," encased in ice and crushed

as if dropped "from an aeroplane." A denouement, by then far from original and

already utilized twice before by the author himself. Thus, even though "Beyond

the Threshold" is wonderfully realized as a story, it still breaks no new ground

in extrapolating on Lovecraftian Mythos lore.

"Dweller in Darkness," on the other hand, ends much more

inventively,even moreso than "The Return of Hastur" and "The Sandwin Compact."

For though Nyarlathotep succeeds in "silencing" the intrusive Prof. Gardner –

whose form he can assume (as does the shape shifter for his victim, in "Spawn of

the Maelstrom") – when the Old One attempts to deal with the two young

colleagues in search of the missing scholar, he is foiled by the incendiary

arrival of Cthugha, a fire elemental, summoned by the terrified youths, with the

"posthumous" aid (via a recorded message) of the professor himself! However,

this "new" Old One, invented by Derleth for the occasion, though fancifully

depicted (as a myriad of "living entities of flame"), does seem somewhat deus ex

machina.

Another interesting feature in both "Beyond the Threshold"

and "The Dweller in Darkness" (one also present elsewhere in his Mythos fiction,

but perhaps not employed so puckishly) might be called Derleth's refinement of

the "Escher Effect." A Moebius-like melting of fiction into "fact" and back into

fiction again, and so on. For, besides citing the now obligatory Canonical shelf

of "forbidden texts" (most frequently the dread Necronomicon) – to which the

author himself has contributed Cultes des Goules – with straight face (but no

doubt twinkling eye), Derleth has characters like Josiah Alwyn (who owns a copy)

and Prof. Gardner (who orders one, which has to be shipped by the publishers [Derleth

himself!]) either hold up for examination or refer to H.P. Lovecraft's The

Outsider and Others (Arkham House, 1939) as substantive "proof" that the Old

Gods do indeed actually exist!

However, such glints of humor are rare in Derleth's Mythos

writing, or in anyone else's (including Lovecraft's) for that matter. And

perhaps rightly so, for unless deftly applied, its presence (like an accidental

woodwind squeak marring a swelling Wagnerian theme) would detract, even if

momentarily, from the unified intention toward horror implicit in any serious

Mythos story. Nevertheless, on two other Mythos occasions, in "The Passing of

Eric Holm" (1939) – the author's only pseudonymous Mythos story (published as by

"Will Garth," a house name) – and "The God Box" (1945), Derleth manages to sport

a grin, at the least, as he illustrates what dire consequences can follow when

fools tinker with the Old Ones, whether directly or indirectly. Such as bungling

amateurs like Eric Holm, who can't quite get the Clithanus incantations right,

and pilfering English archeologists like Philip Caravel (in "God Box"), who

opens one Druidic copper box too many.

All humorous grace notes aside, however, after "Beyond the

Threshold" and "The Dweller in Darkness," Derleth never again set one of his

solo Mythos stories in the Midwest, or even just north of there, as he did in

the "Ithaqua" tales. Nevertheless, in "The Whippoorwills in the Hills" (1948)

and "The House in the Valley" (1953), both "Northeastern" Mythos stories, he

does transplant some of his love of small-town rustic life (evident in the best

of his Midwestern regional writing) to New England soil. Where – in the

outskirts of Arkham and Innsmouth – insular little villages still fearfully

believe in the Old Ones or, at the least, that their minions may be nigh. In

both narratives, too, Derleth is also quite adept at capturing the laconic

dialect and dark suspicions of the local residents, united in resenting

"outsiders. Like the relative, in Whippoorwills," in search of his "lost"

cousin, and the painter, in "House in the Valley," needing seclusion to

concentrate on his work. In addition, both stories, besides paying homage to

Lovecraft, also hearken back to one of the latter's influences, Edgar Allan Poe,

for at story's end both of Derleth's "mad as a hatter narrators" – traumatized

by "dream" contact with Cthulhu and charged with brutal murder – have no

conscious awareness of guilt, and lay the blame elsewhere, on the Old Ones, on

their minions, on anyone but themselves.

During this same period (between 1944 and 1957), Derleth

would also begin work on his longest Mythos opus, the "Shrewsbury" series, which

opened with two Weird Tales novellas, "The House on Curwen Street" (1944) and

"The Watcher from the Sky" (1945). In the former, he introduces the scholarly

but activist Dr. Laban Shrewsbury, recently returned after a mysterious

twenty-year absence from Arkham. Even though "blind" – his eyes "lost" during

torture on Celaeno in the Pleiades – the professor can still somehow "see," and

sets about making himself Cthulhu's most formidable adversary.

By means of stealth, cunning, and force (applied wherever

possible), the professor and his newly acquired aides begin to fight back

against Cthulhu's minions, attempting to block all new efforts to free the Old

One from the "exile" imposed by the Elder Gods. On one occasion, the professor

even tries to dynamite one of Cthulhu's "Doorways to the Outside ...." But he

fails completely, bitterly lamenting, "Too little! Too little!" – though he will

try again. In the second "Shrewsbury" episode, "The Watcher from the Sky,"

however, two of his aides fare better, managing (by torching its

star-stone-encircled dwelling) to assassinate one of Cthulhu's frog-like Deep

Ones, who has been masquerading as human in still-haunted Innsmouth.

However, such short-lived victories have little lasting

effect on Cthulhu and his followers, serving only to alert them to the presence

of their enemies, who must then take flight. And that is what the professor and

(in succession) his aides expeditiously proceed to do. First, by swallowing some

of the Elder Gods' "golden mead" (to heighten sense perceptions and allow travel

"among the dimensions"). Next, by calling upon Hastur for help, appealing to him

in the lost "Aklo" language (derived from the chants of the Great Old Ones'

former priests), for the "Unspeakable One," no friend to his fellow Old One

Cthulhu, has been known to give shelter to the latter's foes. Finally, by

blowing upon a strange stone whistle in order to summon Hastur's bat-like

byakhee "steeds," who bear the imperiled to sanctuary in Celaeno, the faintest

star in the Pleiades cluster of the Taurus constellation. There, most likely on

one of its planets, they wait, until the time is right to do battle again with

the Lord of R'lyeh.

After 1945, however, Derleth would leave off writing about

the Dr. Shrewsbury's guerrilla warfare strikes against Cthulhu. He devoted his

energies to the New England "regional" Mythos stories and the "English" tales –

one of them, "Something from Out There" (1951), essentially a reworking of the

"monster in the abbey ruins" theme of "Those Who Seek," his first Mythos story,

written almost two decades earlier. As well as to "Something in Wood" (1948),

marginally interesting today for its allusions to early Lovecraft acolyte Clark

Ashton Smith, and for the few glimpses it affords of Derleth's familiarity with

the art and music of his day.

But six years later, in 1951 – most likely with the idea of

expanding the series into a "novel" – Derleth revived Laban Shrewsbury, though

perhaps somewhat hesistantly. No doubt recognizing, thorough professional that

he was, the difficulties inherent in devising new adventures based on the

premise set in the first two tales. For how – he must have asked himself – does

one tell basically the same story five times in a row without repeating oneself?

Particularly when it is a Mythos story, which by this time, not only for himself

but for other Lovecraft emulators, had become rather formulaic, every ending –

almost without exception – a foregone conclusion. With the Old Ones and their

minions basically unharmed and their frustrated adversaries always forced to

take flight. And, in Cthulhu's case, with his followers, almost without missing

a beat, stealthily returning to continue work on completing the Grand Design –

freeing the awesome Old One from his undersea "tomb."

"The Testament of Claiborne Boyd" (Weird Tales, 1949),

Derleth's third attempt to resolve some of these problems, didn't go too well.

The least original and most clearly repetitive of them all, this new

"Shrewsbury" novella simply shifts the customary New England setting to New

Orleans and South America, and introduces a new "assistant," a student of Creole

culture in the Mississippi bayou country. Whose curious legacy – the usual at

first puzzling documents and such bequeathed by his late great-uncle, formerly

on the faculty at Arkham's Miskatonic University – plunges Claiborne Boyd into

the thick of things. All of it familiar Mythos trappings, though with one

unusual difference. For instead of playing a central role in this new adventure

(indeed, in the previous episode, he wasn't present at all!), Dr. Shrewsbury

remains on Celaeno throughout, remotely influencing events on Earth from afar.

Communicating with Claiborne Boyd through the latter's

dreams, the professor advises his willy-nilly new assistant on the best way to

evade the approaching enemy, on how to blow up (Shrewsbury's forte) a Peruvian

Cthulhu "doorway," and, finally, how to shoot to death yet another batrachian

Deep One, this one disguised as a religious leader. But in the end, the outcome

mirrors that of the first two Shrewsbury adventures, for like his predecessors,

Claiborne Boyd must hastily summon Hastur's byakhee "steeds" and join the

professor and his allies in safety on Celaeno.

However, in the final two "Shrewsbury" stories, "The Keeper

of the Key"(1951) and "The Black Island" (1952), even though both are replete

with the by now inescapable appurtenances of the series, Derleth finally finds

the way. First, he diversifies the story locales, leaving the Western Hemisphere

behind altogether, setting one episode primarily in Arabia, the other at various

points in the Pacific. Next, he transports Shrewsbury back to earth and –

despite the introduction of two new assistants, each of whom tells his own tale

– gives the professor the central role in the events leading up to the

cataclysmic conclusion near Ponape.

However, in "The Keeper of the Key," Derleth makes a

startling disclosure. In all the previous Shewsbury episodes, the professor and

his aides had never left this planet at all! Only their "life essences, souls,

astral selves" made the light-years' journey to Celaeno. All the while, back on

Earth, their physical "shells" lay safely stored in wooden sarcophogi hidden in

underground tunnels buried deep beneath the sands of Arabia. Waiting, when

needed, to be reclaimed.

And it is in those subterranean passageways lying far below the "Nameless City"

(see Lovecraft's 1921 story, so titled) that Dr. Shrewsbury makes two major

finds. He and his new aide, novelist Nayland Colum – whose Mythos narrative, The

Watchers on the Other Side, has attracted the unwelcome notice of Cthulhu's

followers – discover not only the original manuscript of the Necronomicon but

the actual remains of its author, the Mad Arab Abdul Alhazred himself! Whom the

professor quickly proceeds to conjure the "spectre" of in order to learn the

true location of R'lyeh, Cthulhu's lair beneath the sea.

In the final Shrewsbury novella, "The Black Island," the

professor and his aides (the count now up to four) "return" from Celaeno to do

final battle with Cthulhu. In order to pinpoint R'lyeh's exact location,

Shrewsbury takes on yet another assistant, the young American archeologist

Horvath Blayne, whose knowledge of the Ponape region will be invaluable. Guided

by the Abdul Alhazred map and aided by Blayne's "instincts" (he as yet doesn't

know his true "tainted" Innsmouth heritage), the Cthulhu hunters finally locate

R'lyeh, the ruins of a black stone structure on an uncharted island which has

recently re-surfaced due to earthquake activity in the area.

Wasting no time, the professor and his men go ashore, set

explosive charges about the alien "building," and hastily return to their boats.

None too soon, for emerging swiftly out of the structure's dark portal is a

horrifying protoplasmic mass of tentacles, Cthulhu himself! At that moment,

Shrewsbury gives the signal, the explosives are detonated,and the Lord of R'lyeh

is blown apart, but not for long. For in the twinkling of an eye, the shattered

mass quickly begins to reconstitute itself and swell up to gigantic proportions,

overflowing almost the entire surface of the island.

But the professor (apparently with powerful connections in

Washington)is not discouraged. As back up, he has arranged for a nuclear bomb to

be dropped on Cthulhu's island. And the colossal detonation, the towering

mushroom cloud, and the blasted remains of R'lyeh (still visible as the island

sinks back beneath the waves) give every sign that at last the Old One has been

destroyed, this time for good. However, Horvath Blayne (born an Innsmouth

"Waite"), deep in his DNA, knows better, for his guilt is great. He has betrayed

his heritage by participating in this attack upon Cthulhu. But still he senses

that somehow the Old One has survived even nuclear holocaust. And he "knows"

that someday soon he must pay for his treachery, for there is no escape for the

likes of him, not even to Celaeno.

Up to this point – the final phase in Derleth's development

of his own Mythos stories – most of his protagonists, whether inquisitive

scholars or descendants ignorant of family ties to the Old Ones, have tended to

recoil from their first encounter with the cosmic. But with the character of

Horvath Blayne (narrator of the final Shrewsbury episode), a significant shift

in attitude becomes increasingly apparent. For unlike the author's previous

protagonists descended from a "corrupted" family line, Horvath Blayne, even

before he learns the truth about himself, is subtly "responsive" to Cthulhu's

call, rather than feeling threatened by it. But not strongly enough, for he

betrays the Old One and must be punished for it.

Five years later, in "The Seal of R'lyeh" (1957), the coda to

his Mythos work, Derleth would elaborate on this new idea, carrying it – through

the person of young Marius Phillips – to its logical conclusion. Yet another in

the author's gallery of "tainted" Innsmouth portraits, Marius knows nothing of

his blighted heritage. Even when he discovers, in his deceased Uncle Sylvan's

journal (which is packed, of course, with notes on Old Ones lore), that the old

fellow had been searching for a place called "R'lyeh," he still refuses to

"believe." However, things change when, in quick succession, he finds a "wizard"

ring (which puts the wearer in touch with a terrifying "presence" nearby) and,

under the house, a secret passage to the sea, which, he assumes, his uncle used

in the search for R'lyeh.

However, by far, the most important factor influencing the

progress of Marius' enlightenment is his meeting with Ada Marsh, one of

Derleth's most intriguing female characters and the only one of consequence in

all of his Mythos writings! Although she is described as "not a good-looking

girl," with her "wide, flat-lipped mouth ... and undeniably cold eyes," at first

sight of her faintly frog-like appearance, rather than being repelled, Marius is

strangely attracted to her, though unable as yet to understand why. But soon,

once his own metamorphic changes begin to match her own, he will know better.

And when that takes place, though only Ada realizes it now, these "children" of

Cthulhu (which is what they've become) must go forth – in answer to his "call" –

and seek the Old One wherever his watery kingdom may lie.

And that – once Marius, like Ada, becomes amphibious – is

just what they set out to do, convinced that R'lyeh lies not below Devil Reef,

but somewhere in the North Pacific. Making good use of Uncle Sylvan's ample

legacy, they charter a ship, explore Polynesia's uncharted regions, and near

Ponape discover a strange basaltic island, in the waters below which they find

R'lyeh at last! Standing upon a great undersea slab within one of the oldest

monolithic structures, they listen in awe, as from below come the sounds of a

"vast amorphous body, restless as the sea, stirring in dream ...." The Old One

himself! But dare they break the seal and enter that mighty presence? At this

point in the narrative, Marius Phillip's manuscript ends, leaving one to wonder

how Derleth meant "The Seal of R'lyeh" to be taken. As a Cthulhu minion's paean

to an Old One, or something much darker? For Derleth adds a final note to the

story – one severely undercutting its apparently euphoric surface effect. A

newspaper extract revealing that the last anyone saw of both Mr. and Mrs. Marius

Phillips (and she with child) was when they were cast up out of the deep on a

gigantic geyser and then sucked back down again into the depths. So much for

purblind faith in the Old Ones.

Thus, with his final solo Mythos story, Derleth, though

sometimes accused of tampering with it too freely, seems to share his mentor's

basic vision, depiciting the Old Ones – in "The Seal of R'lyeh," at least – as

being so remote from Mankind's petty concerns that with cosmic indifference and

without compunction they crush both "friend" as well as foe.

– Joseph Wrzos

Saddle River, NJ

September, 1998